China: Good money after bad

One of the most useful reference books any 19th-century collector could possess was the Reverend Robert Brisco Earée’s authoritative study of forgeries and bogus issues, first published in 1882 and unforgettably titled Album Weeds.

And if you want to appreciate just how valuable this kind of research was to early philatelists, you need look no further than the curious Amoy, Shanghai, Ningpo & Hong Kong locals.

Earée reflected nostalgically on these stamps, recalling that in his youthful days they were listed in many catalogues, prominently advertised for sale, and became a staple element of junior collections.

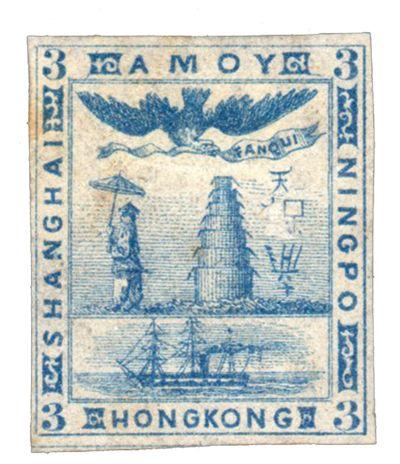

Nicely lithographed on thin white paper, imperforate and usually uncancelled, they might naturally be placed in an album to rub shoulders with the classic 1865 Dragon issue of Shanghai, to which their layout appeared broadly similar. In place of a dragon of tortuous curves and embellishments, however, this extraordinary design had a medley of all things Chinese.

The outer frame bore the names of three of the five British-controlled Treaty Ports established in 1842 at the end of the First Opium War (Amoy, Shanghai and Ningpo), and that of the island simultaneously ceded to Britain (Hong Kong).

In the corners were the figures of value, in numerals but with the unit of currency unstated. Three values exist: the 3 in blue, the 5 in red and the 10 in yellow.

Within the frame are several contrasting scenes. In the centre a cultured mandarin strolls, with unfurled sunshade, past a pagoda that resembles a tower of saucepans. To the right is a jumble of Chinese characters, only the top one of which makes any kind of sense, suggesting heaven. In the bottom panel is a more ominous image of a man-of-war steaming menacingly to the left.

The bizarre jumble of images seems to convey a hidden message from far-off days, but what message? The best clue is at the top, where an eagle is depicted with outstretched wings, carrying a banner in his beak. As it swoops the banner unfurls, revealing the word ‘Fanqui’: a most unflattering epithet used by the Chinese to describe the foreign barbarians in their backyard!

Yes, however believable to the uninitiated, this issue is entirely bogus, and Earée’s work ensured that it is no longer catalogued. Not that this stops it being worth money: good specimens reaching the philatelic market today can fetch up to £100.