National mourning

Sir Winston Churchill was 90 years old when he died on January 24, 1965. Remarkably, he had been a member of the House of Commons until as recently as the previous autumn.

As Britain’s greatest parliamentarian and war leader, not to mention a Nobel Prize-winning author, a journalist and an accomplished artist, he was an obvious subject for a set of stamps, but the Post Office established a new precedent in issuing them.

In the field

No-one packed so much into one life as Churchill.

Educated at Harrow and Sandhurst, he was commissioned into the Fourth Hussars in 1894 and sent to India. Chafing at inactivity and seeking action, he went to Cuba in 1895 as a military observer during the war between Spain and her rebellious colonists.

Later he saw active service on the North-West Frontier, which became the subject of his first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force. And he took part in the last ever cavalry charge of the British army, at Omdurman in the Sudan, recorded in his two-volume The River War.

As a war correspondent during the Boer War, he was captured by the enemy and made a sensational escape which hit the headlines. As well as giving him a theme for another couple of books, this undoubtedly helped him win election to parliament in 1900 as the Member for Oldham.

Not that his military career was over. When out of ministerial office in the latter half of World War I, he volunteered for active service and commanded the 6th Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front.

In the house

A Conservative who switched to the Liberals, then later returned to the Tory fold, Churchill had a rollercoaster political career that would have crushed a lesser man.

He held almost every major ministerial post from Under-Secretary for the Colonies in 1905 to Prime Minister from 1940-45 and 1951-55. But it was by no means a smooth progression.

As First Lord of the Admiralty from 1914 he was the minister responsible for the Gallipoli disaster. Later, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he was responsible for Britain returning to the gold standard, which led to inflation, depression, unemployment and the General Strike in the 1920s.

He was frequently at odds with successive Prime Ministers and cabinet colleagues, and was out of office again in his ‘wilderness years’ from 1929 until 1939. He devoted much of this time to writing his History of the English-Speaking Peoples, which earned him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953.

But his finest hour arrived in 1940, when he succeeded Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister in the early stages of World War II and began to forge his reputation as a great war leader.

In the memory

In death, Churchill was the first commoner to be accorded a state funeral since the death of Lord Roberts in 1914.

And it turned out to be the grandest such affair the world had yet seen, attended by royalty and heads of state from many countries and remaining unsurpassed until that of Pope John Paul II in 2005.

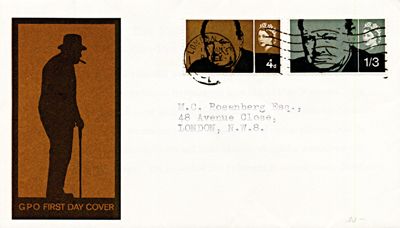

The Royal Mint struck a crown coin in his honour, and the Post Office decided to issued Great Britain’s first ever mourning stamps.

This comprised two values: a 4d black and olive-brown and a 1s 3d black and grey, issued with or without phosphor bands.

The lower value was printed by Harrison & Sons on two different machines. Stamps from the Rembrandt machine generally lack the shading on the face, whereas those from the Timson press show more detail, notably the furrow on Churchill’s forehead and a better delineated left eyebrow.

A good proportion of the Rembrandt machine’s 4d stamps have been recorded with the watermark inverted; this variant also occurs on the 1s 3d, but is much less common.

First-day handstamps from the larger post offices were already well-established, but on this occasion the Post Office also provided a handstamp from Bladon, Oxfordshire, where Churchill was laid to rest, not far from his birthplace at Blenheim Palace.