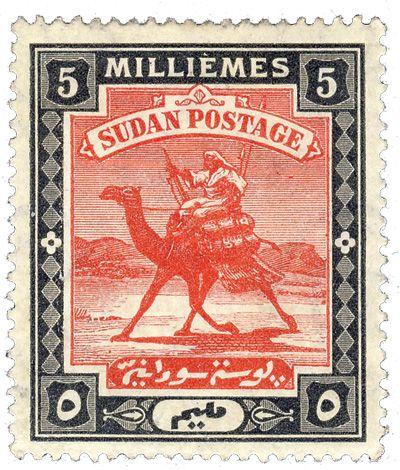

Sudan: Designed on the hoof

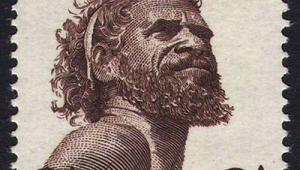

It was under Egyptian rule that Sudan’s first post offices opened in 1867, using a combination of Egyptian stamps and local cancellations. In this vast territory of nearly a million square miles and arduous desert terrain, the camel was the means by which the mail was delivered over long distances.

There was British involvement in the Sudan in the 1870s, as Colonel Charles Gordon was appointed Governor of the country by the Khedive of Egypt, but direct responsibility came only after British forces occupied Egypt in 1882.

Within three years, a revolt led by Muhammad Ahmad, the self-styled Mahdi, had resulted in the death of Gordon and the fall of Khartoum in 1885. Under Mahdist rule the postal service collapsed, and it would take the return of the British to restore it and to introduce Sudan’s first stamps.

In 1896, an Anglo-Egyptian force set off under the command of General Sir Herbert Kitchener, and it was during this long campaign that Sudanese philately was reborn.

At first, soldiers’ letters were sent home stampless, but it wasn’t long before Kitchener was considering the postal system that Sudan would need after the reconquest.

He liked the pen-and-ink drawings with which Captain Edward Stanton embellished the margins of his survey maps, so Stanton was summoned and given five days to come up with a stamp design.

Three days passed and Stanton was without inspiration, until he watched the arrival of camp mail by camel postman. Persuading a local sheikh to ride up and down in front of him, with sacks of straw substituting for mailbags, he made a rapid sketch.

Kitchener liked it, and sent it to De La Rue in London for engraving and printing by typography. Eight values, from 1-millieme to 10-piastres, each in two colours, were printed on wove paper perforated 14.

On two of the mailbags, Stanton had optimistically inscribed the names of Khartoum and Berber, towns which were then still in Mahdist hands. To his amazement, the engraver had managed to incorporate these, in tiny lettering, in the finished design!

On March 1, 1898, the stamps went on sale in Berber, for by then Stanton’s optimism had become reality and the town was indeed in British hands. The end of the brutal Mahdist regime duly came in September, with its defeat at the ferocious Battle of Omdurman.

Despite its rushed design, the Camel Postman would become one of the world’s most recognisable definitive issues. And it would last a century, far outliving British control of Sudan.

One unforeseen problem with the first issue concerned the Rosette watermark, which looked like a cross and caused consternation to Muslim stamp users. But that was quickly rectified by adopting a new Star & Crescent watermark in 1902.

Smaller-format lower values appeared in 1921, dubbed ‘Small Camels’ to distinguish them from the original ‘Large Camels’ with their 25mm x 30mm frame size.

During World War II, De La Rue’s London printing works were bombed, and definitives with a different design were printed in India. By 1948, however, the Camel Postman was back, redesigned for its own golden jubilee.

It remained the design choice for the 50p top value of 1951, and remarkably survived the arrival of self-government in 1954 and independence in 1956, to be reused in the 1962 and 1991 series.

These stamps can also be found overprinted (or in some cases with perforated initials) for Government Service from 1900-62, Army Service from 1905-24 and Air Mail in 1931, and surcharged on various occasions between 1903 and 1941.

Like the animal it illustrates, the design is a fine example of service and endurance.